Presentation at the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA) & Gesellschaft für Fantastikforschung (GfF, or German Association for Research in the Fantastic) joint conference “Disruptive Imaginations” in Dresden, Germany. Great to be back at an in-person event! This conference was special for me because in 2010 I presented a paper at the inaugural GfF conference in Hamburg.

Overview

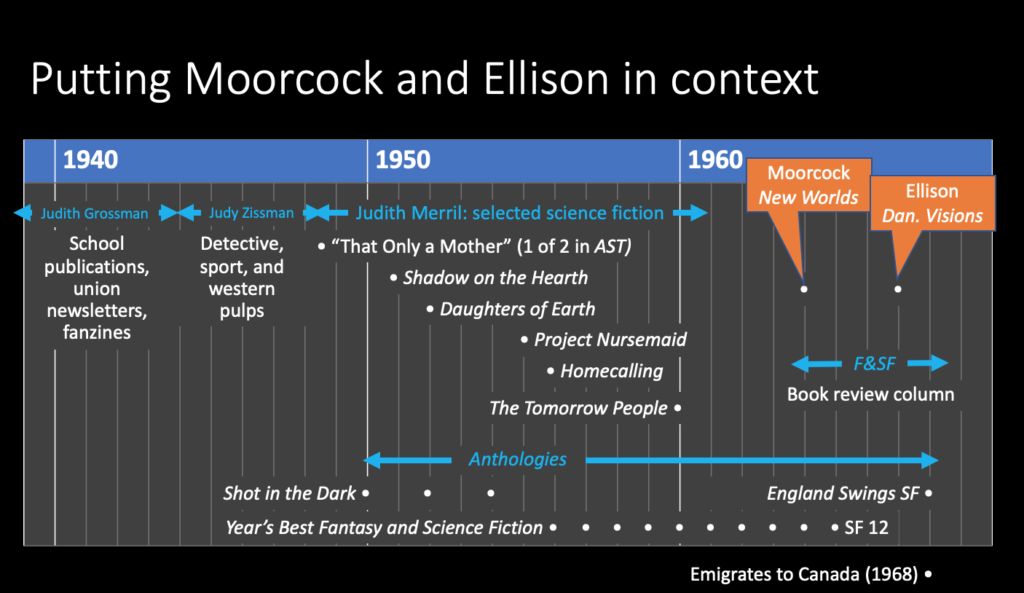

In the 1960s, a supposedly new kind of science fiction under the rubric of the “new wave” drew substantial attention as an alternative to the golden age aesthetic, as promoted by John W. Campbell. Michael Moorcock in the UK and Harlan Ellison in the US came on the scene with visions of brash, manly individualism that they hoped would bring science fiction to a wider audience. As science fiction found its way into university courses and academic studies of the 1970s, this vision became enshrined as an important disruption.

The way in which Moorcock and Ellison sought to gain a wider audience for science fiction, though, seems less than disruptive in the broader context of cultural studies. In the 1960s, a new vision of masculinity became prominent, turning against fatherly figures like President Eisenhower. For instance, Arthur Schlesinger’s “The Crisis of American Masculinity” (1958) suggested that Cold War men needed to accustom themselves to uncertainty and discontinuity. President-Elect John F. Kennedy wrote “The Soft American” for Sports Illustrated(1960) to tie manly American individualism to the fight against communism. In this way, the aesthetic of Moorcock’s The Black Corridor and Ellison’s “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” is in continuity with, not disruptive of, the overall culture.

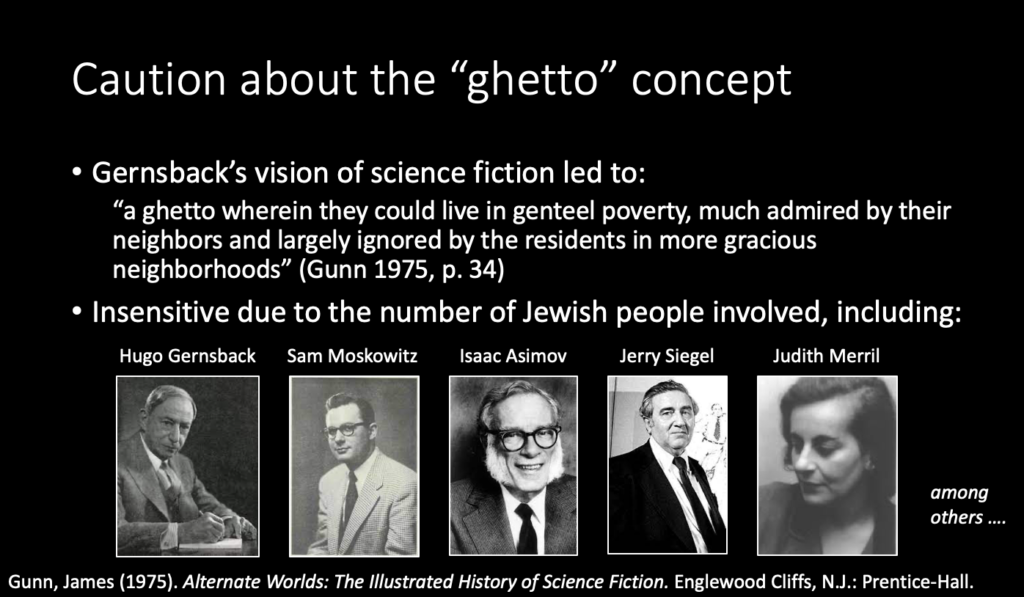

Something unusual about this supposed disruption is the way that Judith Merril is considered to be a collaborator in the new wave, even though she never used this term herself, preferring the vaguer “the new thing.” Ellison, without crediting her, mimicked many of her ideas. Considering the broad scope of Merril’s editorial career, starting from her first anthology, “Shot in the Dark” (1950), through the dozen “year’s best” anthologies she edited, it seems like Merril was herself more disruptive, creating a space for genre-busting fiction authors who were not aiding cold war ideologies. Although Moorcock’s criticism of golden age of science fiction are valid – see, for instance, his “Starship Stormtroopers” essay – it is unclear how disruptive the fiction written and promoted by him and Ellison was as disruptive as they proclaimed it to be. Merril, however seems to be the true disruptor, especially considering today’s desire to broaden definitions of science fiction.

Selected Slides

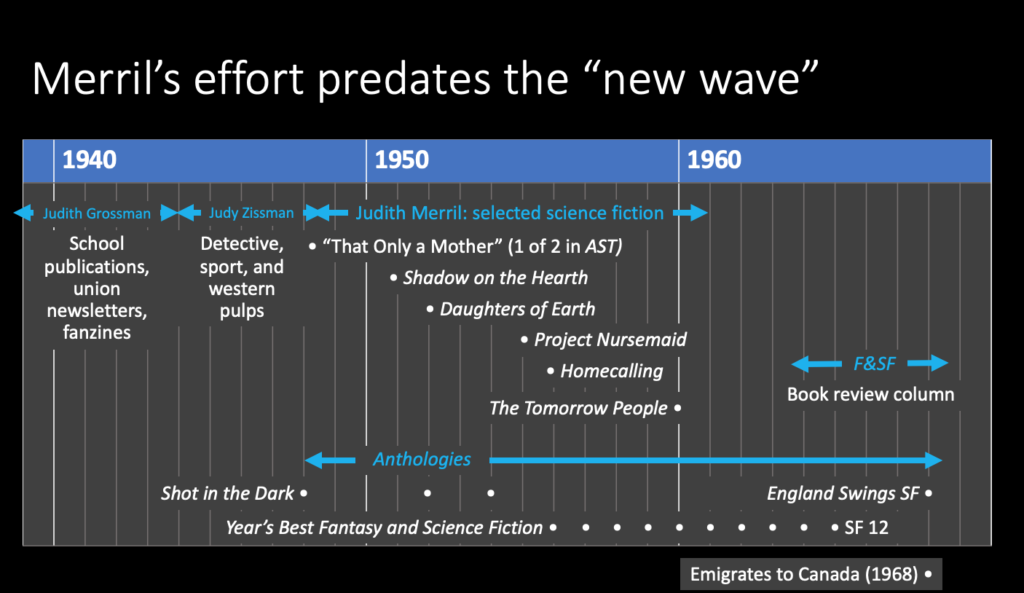

As detailed in Chap. 7 of my book, From Hyperspace to Hypertext, Merril promoted the “new thing” in science fiction for many years – both as a writer and as an editor. Ellison and Moorcock, although they borrow some of Merril’s ideas, come on the scene much later.

Photos

In between the time I submitted my abstract and my conference presentation, my academic affiliation changed. Glad I was able to attend anyway.

I visited Dresden during my 2008-2009 Fulbright year at Universität Potsdam, but only a day trip. Grateful for the chance to spend a few days there.