Home

Restoring the Unspoken Context of Early Science Fiction

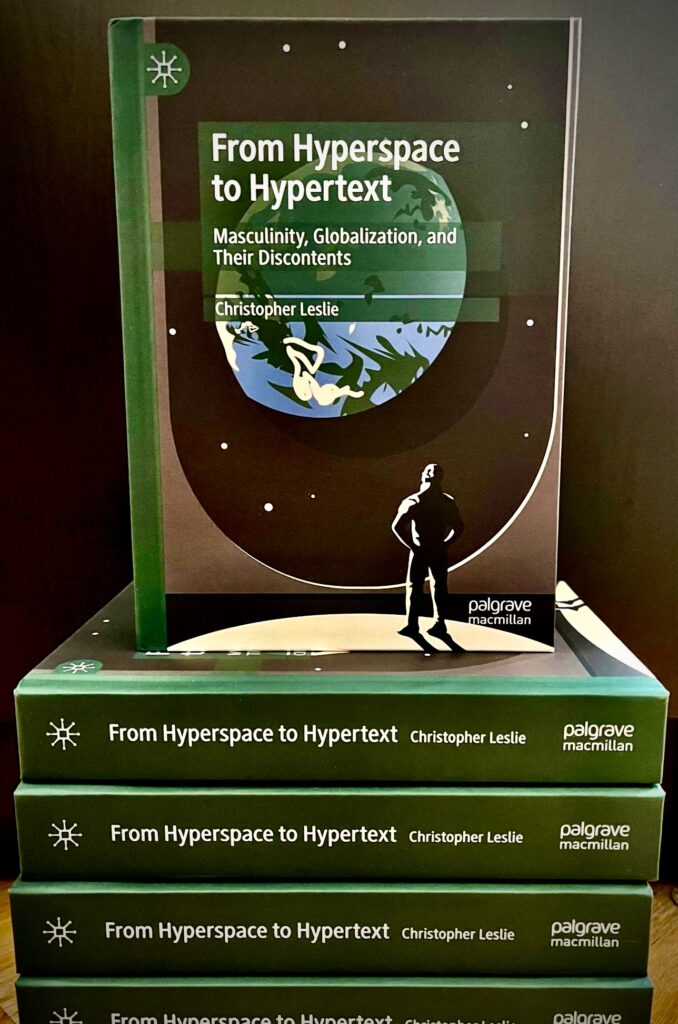

From Hyperspace to Hypertext: Masculinity, Globalization, and Their Discontents illustrates how science fiction studies can support diversity, equity, and inclusion in science and engineering. The book is available now as an e-book through more than 15,000 institutions worldwide, from Palgrave Macmillan directly, and from online bookstores.

Shortly before science fiction got its name in 1929, a new paradigm in the popular imagination connected whiteness, masculinity, and the advancement of civilization. Strangely enough, however, a growing scientific consensus had begun to show the fallacies in this thinking. As scientists amassed evidence that showed race and gender did not determine individual aptitudes and the destinies of groups, science fiction authors clung to outdated racist and sexist beliefs.

That being said, there were some authors who adroitly challenged the persistence of this paradigm from within the genre. Unfortunately, their work was marginalized by fan historians and editors after World War II. Putting the early history of U.S. science fiction into conversation with the debate over white masculinity offers provocative insights into these works.

Supported by a fresh look at archival sources and author’s experience teaching Science and Technology Studies at universities on three continents, From Hyperspace to Hypertext demonstrates the interconnections among discourses of imperialism, masculinity, and innovation. Readers gain insights into fighting prejudice, the importance of the community of authors and readers, and ideas about how to challenge racism, sexism, and xenophobia in new creative work. Overall, the book shows how education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) can be enhanced by adding the liberal arts, such as historical and literary studies, to create STEAM.

The book is divided into three parts, with each one devoted to a major editor: Hugo Gernsback, John W. Campbell, Jr., and Judith Merril.

Part I. The Gernsback Era

Chapter 1: Cosmopolitan Gentlemen of Science. At the same time when Hugo Gernsback came to the United States in 1904 in pursuit of economic opportunity, novel ideas about the connection between white men and civilization were circulating. As he directed his business interests toward publishing, he supported nineteenth-century thinking about civilization and human difference. His fiction and his editorial choices provide an invaluable window onto how a definition of progress naturalized the tie of white masculinity to civilization.

Chapter 2: Planet Smashers of the Second Industrial Revolution. Despite the frequent assertion that Hugo Gernsback demanded scientific accuracy in science fiction, the authors he published did not convey new scientific thinking—particularly where new insights were threatening old paradigms regarding sex and race. Authors like E. E. “Doc” Smith became famous for fiction that supported the supposed connection between science, civilization, and masculinity. The fan serial Cosmos, drawing as it did from many of Gernsback’s early authors, is remarkable for its use of these themes.

Chapter 3: Have We Not Had Enough of War? There were significant dissenters to the new paradigm. The three discussed in this chapter—Claire Winger Harris, Leslie F. Stone, and L. Taylor Hansen—played important roles in Gernsback publications. When these authors worked with Gernsback, they crafted fiction skeptical of the connections between masculinity, whiteness, and civilization. Accordingly, they were not always popular with fans. They and their stories were largely written out of the genre after World War II. In the context of this study, though, their work is remarkably effective challenge to the new paradigm.

Part II. The Campbell Era

Chapter 4: Archeology of the Future. John W. Campbell, Jr., the second editor considered in this study, experienced the new paradigm of manliness and civilization both as a physics undergraduate student and through the fiction promoted by Gernsback. Even though the fallacies that supported the paradigm were no longer accepted in the scientific community, Campbell’s work was held out as an exemplar of scientific rigor. Learning to reevaluate his legacy provides a window onto the subtle synergy among racism, sexism, and imperialism in the writers he promoted as editor as well as in the STEM professions generally.

Chapter 5: The Editor with One Hundred Hands. The success of Isaac Asimov, one of Campbell’s most successful recruits, had a price: he turned away from his early fiction that addressed themes of prejudice and racialization. He was also a public harasser of women, and he became known as the man with a hundred hands. As anthology editor, he effectively silenced many women authors, and he was also unwilling to publicly confront Campbell’s biases, even though he was well aware of their scientific bankruptcy.

Chapter 6: The Challenges of Inclusion. The careers of C. L. Moore and Leigh Bracket share at least one thing in common: both were used to support the idea that women writers of science fiction before 1970 had to conceal their sex in order to be published. As is shown in this chapter, both writers were open about their sex. Both authors also wrote superb critiques of golden-age science fiction and illustrate an alternative, the culture concept, well.

Part III. The Merril Era

Chapter 7: Confronting Cold War Masculinity. Although some have tried, it should be impossible to tell the story of U.S. science fiction without Judith Merril, the third editor considered in this study. Facing a new vision of masculinity promoted during the atomic age and the space race, Merril brought attention to how the new paradigm threatened science fiction. Countercultural and concerned with human values, Merril became increasingly an advocate for a genuine cosmopolitanism that found golden-age science fiction notions of globalism naïve.

Chapter 8: The End of Science Fiction. In her role as critic and editor, Merril showed increasing antagonism to the label “science fiction.” The diverse writers promoted by Merril—including Katherine MacLean, Carol Emshwiller, Samuel Delany, Theodore Sturgeon, J. G. Ballard, and Cordwainer Smith—demonstrate a divergence from other authors championed by what came to be known as the new wave. In this way, they are case studies for others who wish to analyze and create fiction that challenges recent ideologies of race, sex, and gender.

Chapter 9: Science Fiction and the University. As she was emigrating to Canada, Merril’s challenges to golden-age science fiction should have been ascendant. New developments in science and technology studies would come to challenge the determinist and colonialist assumptions that permeated so much of golden age writing. However, it would be many years before science fiction would catch up. This is clearly seen in two incursions science fiction makes into universities: computing and science fiction studies. Today, however, university studies of science fiction share with Merril the desire for a broader canon and the focus on what it means to be human.